Perhaps we can answer Rav Shteinman’s question to some extent by appreciating exactly the nature of what a bracha is. The Arizal explains that making brachos are one of the foundations of service of Hashem.[2] Moreover, a bracha is our way of connecting with Hashem by verbally appreciating what He has done for us. Reciting a bracha requires us to actually think about what Hashem has done for us. For example, when making a bracha over food, we can come to recognize that the Creator of the World gives us tasty food, when He could have just sustained us on bland sustenance.[3] By making a bracha on our daily actions, we imbue Godliness into our lives by stopping for a moment and appreciating all that Hashem is doing for us. By saying a bracha properly with this in mind, our entire lives will be changed. We will be living with a constant awareness of the kindness that Hashem is bestowing upon us all the time.

Perhaps, therefore, this is the answer we can provide why the Jewish People were complaining about something so seemingly inconsequential as a bracha. Because, in reality, a bracha is not inconsequential at all. It is a Jew’s key to connecting with Hashem throughout the day. When the Jews were in Egypt, they were subjugated to forced labor. They were told exactly what to do and when to do it. Part of Pharaoh’s plan in enslaving the Jewish People in such a way was in order to take away all of their ‘free’ time to stop and pray to Hashem. To this degree, life was a lot easier in Egypt; there was no time to think about what to do – everything ran on cruise control. Every morsel of food was gobbled down just to survive, with no time to think.[4]

However, when the Jews were required to say brachos this was a complete mind shift in their relationship with Hashem. They actually had to stop and think about their lives for they now had the ability to choose how to live. With this great power came great responsibility — and great risks, for the consequences of not taking the opportunity of getting close to Hashem when it is presented are that it acts as an active disassociation with Him. Therefore, perhaps it was out of this fear that the Jewish People were reluctant to accept upon themselves the obligation to makebrachos.

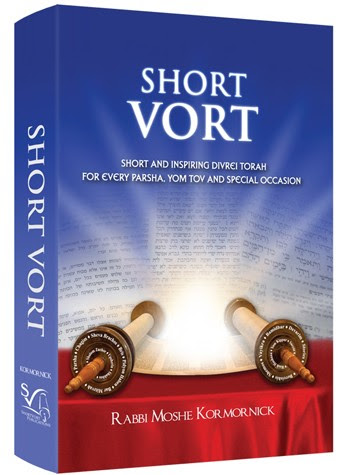

Rabbi Moshe Kormornick, is the best selling author of SHORT VORT, available in Jewish bookstores worldwide, as well as at Feldheim.com and on amazon.

The book contains over 340 pages of Short Vorts and stories on every Parashah, Yom Tov, and Simcha.

And it’s under $10!

Proudly published by Adir Press. To publish your book, click here